Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 stem–loop 5 (SL5) (PDB id: 9E9Q; Jones CP, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. 2025. Crystallographic and cryoEM analyses reveal SARS-CoV-2 SL5 is a mobile T-shaped four-way junction with deep pockets. RNA 31: 949–960). The T-shaped four-way junction of the coronavirus SL5 structural element provides a starting point for examining the structures of larger RNA motifs and their interactions with other molecules. Image highlighting the four arms of the junction. The RNA backbone is depicted by a gray ribbon. The bases within the arms of the junction are colored respectively in blue, red, yellow, and cyan. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for Structural Bioinformatics of Nucleic Acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

As the developer of DSSR, I am thrilled to see its application in cutting-edge research across multiple disciplines. Below is a list of four recent publications that highlight how DSSR has been utilized, underscoring its versatility and significance in structural bioinformatics.

In the Geng et al. (2025) Nucleic Acids Research (NAR) paper, titled 'Revealing hidden protonated conformational states in RNA dynamic ensembles', DSSR is simply cited as follows:

All bp geometries, hydrogen-bond, backbone, stacking, and sugar dihedral angles were calculated using X3DNA-DSSR [77].

In the preprint by Gordan et al. (2025), titled 'High-throughput characterization of transcription factors that modulate UV damage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution', DSSR is cited as follows:

Step base stacking, base pair shift, base pair slide, interbase angle, pseudorotation angle, and sugar puckering classifications of nucleobases were computed using X3DNA-DSSR (v2.5.0)75. Base stacking was defined as the overlapping polygon area in Å2 when projecting the dipyrimidine base ring atoms (excluding exocyclic atoms) into the mean base pair plane76. The sugar ring pseudorotation phase angle of each pyrimidine was also calculated using X3DNA-DSSR as described by Altona, C. & Sundaralingam, M.77 Interbase angle was defined as sqrt(propeller2+buckle2) per the X3DNA-DSSR documentation.

Figure 6: TF Binding Induces Structural Distortion Favorable to UV Dimerization is highly informative, particularly panel (a), which illustrates the ensemble of structural parameters that predispose dipyrimidines to cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD) or 6-4 pyrimidine-pyrimidones (6-4 PP) formation. DSSR is designed as an integrated software tool, offering a comprehensive suite of structural parameters not found in any other single tool I am aware of. Despite this, the innovative use of DSSR by Gordan et al. exceeds my expectations and demonstrates its versatility.

In the preprint by Kubaney et al. (2025) from the Baker group, titled 'RNA sequence design and protein-DNA specificity prediction with NA-MPNN', DSSR is cited as follows:

On the pseudoknot subset, we evaluate additional structure‐ and reactivity‐based metrics. DSSR v2.3.241 is used to extract the ground‐truth secondary structure from the native crystal structures. For each designed sequence, RibonanzaNet predicts 2A3 reactivity profiles, from which we compute predicted OpenKnot scores (see https://github.com/eternagame/OpenKnotScore)31 using the predicted reactivity together with the DSSR ground truth.

In a recent NSMB paper from the Baker group, titled 'Computational design of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins', 3DNA is cited as follows:

RIF docking of scaffolds onto DNA targets (DBP design step 1) Structures of B-DNA for each target (Supplementary Table 2) were generated by (1) using the DNA portion of PDB 1BC8 (ref. 60), PDB 1YO5 (ref. 61), PDB 1L3L (ref. 51) or PDB 2O4A (ref. 62) or (2) using the software X3DNA63, followed by a constrained Rosetta relax of the DNA structure.

Please note that 3DNA has been replaced by DSSR. The functionality for constructing B-DNA models, previously provided by 3DNA, is now directly available in DSSR via its fiber and rebuild modules.

In the preprint by Si et al. (2025), titled 'End-to-End Single-Stranded DNA Sequence Design with All-Atom Structure Reconstruction', DSSR is cited as follows:

Since ViennaRNA and NUPACK require secondary structures as input, we used DSSR35 to extract secondary structures from the corresponding ssDNA three-dimensional structures.

The above use cases are merely a sample of how DSSR is utilized in the scientific literature. It is reasonable to state that DSSR has emerged as a de facto standard tool within the field of nucleic acid structural bioinformatics. Overall, DSSR is a mature, robust, and efficient software product that is actively developed and maintained. I am committed to making DSSR synonymous with quality and value. Its unmatched functionality, usability, and support save users significant time and effort compared to alternative solutions.

DSSR is available free of charge for academic users. Additionally, it has been integrated into other high-profile bioinformatics resources, including NAKB, PDB-redo, and N•ESPript.

References

- Geng A, Roy R, Ganser L, Li L, Al-Hashimi HM. Revealing hidden protonated conformational states in RNA dynamic ensembles. Nucleic Acids Research. 2025;53:gkaf1366. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaf1366.

- Gordan R, Wasserman H, Chi B, Bohm K, Duan M, Sahay H, et al. High-throughput characterization of transcription factors that modulate UV damage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution. 2025. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-8197218/v1.

- Kubaney A, Favor A, McHugh L, Mitra R, Pecoraro R, Dauparas J, et al. RNA sequence design and protein–DNA specificity prediction with NA-MPNN. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.10.03.679414.

- Glasscock CJ, Pecoraro RJ, McHugh R, Doyle LA, Chen W, Boivin O, et al. Computational design of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2025;32:2252–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-025-01669-4.

- Si Y, Xu Y, Chen L. End-to-end single-stranded DNA sequence design with all-atom structure reconstruction. 2025. https://doi.org/10.64898/2025.12.05.692525.

The latest release, DSSR v2.7.2-2026jan12, introduces the --pair-wise (or --pairwise) option, which combines the functionalities of the previous --pair-only and --non-pair options. Base-pair identification is a cornerstone of nucleic acid structural analysis, while non-pairing interactions like H-bonds and stacking are also vital structural features. However, the DSSR --non-pair feature is underutilized within the user community. By consolidating these into a single --pair-wise option, we streamline the process of identifying common interactions between nucleotides.

DSSR offers a wide range of nucleic acid structural features, but for users focusing on fundamental DNA/RNA analysis and annotation, the --pair-only option provides simplified functionality. This option instructs DSSR to generate only base-pairing information, which is essential for structural studies. When enabled, --pair-only significantly enhances performance, allowing DSSR to run approximately 10 times faster than in its default configuration. Running DSSR on the yeast phenylalanine tRNA (PDB 1ehz) with the --pair-only option leads to the following output instantaneously:

# x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --pair-only

List of 34 base pairs

nt1 nt2 bp name Saenger LW DSSR

1 A.G1 A.C72 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

2 A.C2 A.G71 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

3 A.G3 A.C70 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

4 A.G4 A.U69 G-U Wobble 28-XXVIII cWW cW-W

5 A.A5 A.U68 A-U WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

6 A.U6 A.A67 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

7 A.U7 A.A66 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

8 A.U8 A.A14 U-A rHoogsteen 24-XXIV tWH tW-M

9 A.U8 A.A21 U+A -- -- tSW tm+W

10 A.A9 A.A23 A+A -- 02-II tHH tM+M

11 A.2MG10 A.C25 g-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

12 A.2MG10 A.G45 g+G -- -- cHS cM+m

13 A.C11 A.G24 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

14 A.U12 A.A23 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

15 A.C13 A.G22 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

16 A.G15 A.C48 G+C rWC 22-XXII tWW tW+W

17 A.H2U16 A.U59 u+U -- -- tSW tm+W

18 A.G18 A.PSU55 G+P -- -- tWS tW+m

19 A.G19 A.C56 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

20 A.G22 A.7MG46 G-g -- 07-VII tHW tM-W

21 A.M2G26 A.A44 g-A Imino 08-VIII cWW cW-W

22 A.C27 A.G43 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

23 A.C28 A.G42 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

24 A.A29 A.U41 A-U WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

25 A.G30 A.5MC40 G-c WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

26 A.A31 A.PSU39 A-P -- -- cWW cW-W

27 A.OMC32 A.A38 c-A -- -- c.W c.-W

28 A.U33 A.A36 U-A -- -- tSH tm-M

29 A.5MC49 A.G65 c-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

30 A.U50 A.A64 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

31 A.G51 A.C63 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

32 A.U52 A.A62 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

33 A.G53 A.C61 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

34 A.5MU54 A.1MA58 t-a rHoogsteen 24-XXIV tWH tW-M

With the --non-pair option, DSSR identifies H-bonding and base-stacking interactions between two nucleotides that do not form a pair. This option is an additional feature integrated into DSSR, expanding its capabilities by including these non-pairing interactions in the main output alongside pairing information, among other functionalities. Running DSSR on the yeast phenylalanine tRNA (PDB 1ehz) with the --non-pair option identifies 91 non-pairing interactions, with the first 16 listed below.

# x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb

List of 91 non-pairing interactions

1 A.G1 A.C2 stacking: 5.4(2.6)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=5 connected min-baseDist=3.26

2 A.G1 A.A73 stacking: 2.4(1.2)--mm(<>,outward) interBase-angle=3 min-baseDist=3.17

3 A.C2 A.G3 stacking: 0.5(0.0)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=9 connected min-baseDist=3.41

4 A.G3 A.G4 stacking: 3.2(1.8)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=10 H-bonds[1]: "O2'(hydroxyl)-O4'[3.11]" connected min-baseDist=3.24

5 A.G3 A.G71 stacking: 2.6(0.3)--mm(<>,outward) interBase-angle=5 min-baseDist=3.02

6 A.G4 A.A5 stacking: 5.6(3.5)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=6 connected min-baseDist=3.13

7 A.A5 A.U6 stacking: 5.9(4.3)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=9 connected min-baseDist=3.12

8 A.U6 A.U7 stacking: 0.6(0.0)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=20 connected min-baseDist=3.11

9 A.U7 A.5MC49 stacking: 1.2(0.0)--pm(>>,forward) interBase-angle=7 H-bonds[1]: "O2'(hydroxyl)-OP2[2.68]" min-baseDist=3.64

10 A.U8 A.C13 stacking: 2.0(0.0)--pp(><,inward) interBase-angle=13 min-baseDist=3.34

11 A.U8 A.G15 stacking: 0.5(0.0)--mm(<>,outward) interBase-angle=14 min-baseDist=3.27

12 A.A9 A.C11 interBase-angle=27 H-bonds[1]: "O2'(hydroxyl)-N4(amino)[2.90]" min-baseDist=3.72

13 A.A9 A.C13 interBase-angle=9 H-bonds[1]: "OP2-N4(amino)[3.01]" min-baseDist=4.65

14 A.A9 A.G22 stacking: 0.1(0.0)--mp(<<,backward) interBase-angle=13 min-baseDist=3.37

15 A.A9 A.G45 stacking: 1.6(0.5)--pp(><,inward) interBase-angle=10 min-baseDist=3.30

16 A.A9 A.7MG46 stacking: 1.6(0.7)--mm(<>,outward) interBase-angle=4 H-bonds[1]: "O5'-N2(amino)[3.34]" min-baseDist=3.38

......

DSSR calculates base-stacking by determining the overlap area (in Ų) between two interacting bases. The calculation involves projecting the atoms of the two bases onto their mean plane to define the overlapping region, from which the area is derived. In the output, values in parentheses represent the overlap area based solely on ring atoms, while those outside parentheses include contributions from exocyclic atoms as well (see Lu and Olson, 2003; Lu et al., 2015).

Base-stacking interactions are classified into one of four categories:

- pm (>>, forward): Interaction occurs on the plus-minus faces of the two bases in a forward direction.

- mp (<<, backward): Interaction occurs on the minus-plus faces of the two bases in a backward direction.

- mm (<>, outward): Interaction occurs between two minus faces oriented outward.

- pp (><, inward): Interaction occurs between two plus faces oriented inward.

In this classification:

p represents the plus face of the base ring, andm represents the minus face.

These categories are defined by the direction of the z-axis in the standard base reference frame (Olson et al., 2001). The symbols (>>, <<, <>, and ><) follow Parisien et al. (2009), with the exception that:

- pm (>>) is referred to as "forward" instead of "upward," and

- mp (<<) is referred to as "backward" instead of "downward."

The new --pair-wise option functions similarly to the --pair-only option by generating a separate output file. However, unlike --pair-only, it also includes non-pairing interactions in this file. DSSR runs faster than the full analysis because it characterizes only base-pairing and non-pairing interactions. Additionally, the --more and --json options are supported, enabling users to derive more detailed features (e.g., local base-pair parameters and H-bonds in base pairs) and easily parse them using JSON output.

Running DSSR on the yeast phenylalanine tRNA (PDB 1ehz) with the --pair-wise option identifies 34 base pairs and 91 non-pairing interactions, as expected. When combined with the --more and --json options, the output is summarized below.

# x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --pair-wise --more --json | fx

{

"num_pairs": 34,

"pairs": […],

"num_nonPairs": 91,

"nonPairs": […],

"program": "DSSR v2.7.2-2026jan12 by xiangjun@x3dna.org"

}

Please refer to the DSSR User Manual for comprehensive explanations of all available features.

References

- Lu X-J, Olson WK. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg680.

- Lu X-J, Bussemaker HJ, Olson WK. DSSR: an integrated software tool for dissecting the spatial structure of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;:gkv716. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv716.

- Olson WK, Bansal M, Burley SK, Dickerson RE, Gerstein M, Harvey SC, et al. A standard reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;313:229–37. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.2001.4987.

- Parisien M, Cruz JA, Westhof É, Major F. New metrics for comparing and assessing discrepancies between RNA 3D structures and models. RNA. 2009;15:1875–85. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.1700409.

Recently, I read the preprint of Gordan et al. (2025), titled "High-throughput characterization of transcription factors that modulate UVdamage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution". In the METHODS section on "Structural analysis of AlphaFold 3 predicted TF-DNA complexes", the authors introduced two geometric parameters to characterize dipyrimidines, as detailed below:

Base-step d22 distance, d64 distance, of dipyrimidines were computed for each base-step per DNA strand using custom PyMOL python scripts74. d22 was defined as the distance in Ångstroms (Å) between the C5-C6 bond midpoints between adjacent pyrimidines. d64 was defined as the Å distance between the 5' pyrimidine's C5 and X4 (either O or N) attached to the 3' pyrimidine's C4.

These d22 and d64 parameters are well-defined and straightforward to calculate (see the figure below for illustrative examples). They can be integrated seamlessly with DSSR's infrastructure, requiring minimal additional coding effort. As a result, I have decided to implement them into DSSR.

For example, in the case of the MyoD bHLH domain-DNA complex (PDB ID: 1mdy), running the following DSSR (v2.7.1) command:

x3dna-dssr -i=1mdy.pdb --json -o=1mdy.json

generates a JSON file (1mdy.json), which contains the following information under the nts section for E.DT1 (connected with E.DC2): "d22": 4.014 and "d64": 3.655."

The default human-readable output file,

The default human-readable output file, dssr-torsions.txt, now includes two additional columns for d22 and d64 under the section titled 'Main chain conformational parameters,' as shown below.

nt d22 d64

1 T E.DT1 4.01 3.66

2 C E.DC2 --- ---

3 A E.DA3 --- ---

4 A E.DA4 --- ---

5 C E.DC5 --- ---

6 A E.DA6 --- ---

7 G E.DG7 --- ---

8 C E.DC8 4.13 4.44

9 T E.DT9 --- ---

Note that pseudouridine (Ψ) is excluded from the calculation of d22 and d64 parameters of a dipyrimidine base step.

The implementation of d22 and d64 parameters in DSSR is a clear example of my proactive approach to enhancing the software's functionality. Users are always encouraged to reach out with requests for new features or improvements, as well as to report any bugs or ask questions.

References

- Gordan R, Wasserman H, Chi B, Bohm K, Duan M, Sahay H, et al. High-throughput characterization of transcription factors that modulate UVdamage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution. 2025. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-8197218/v1.

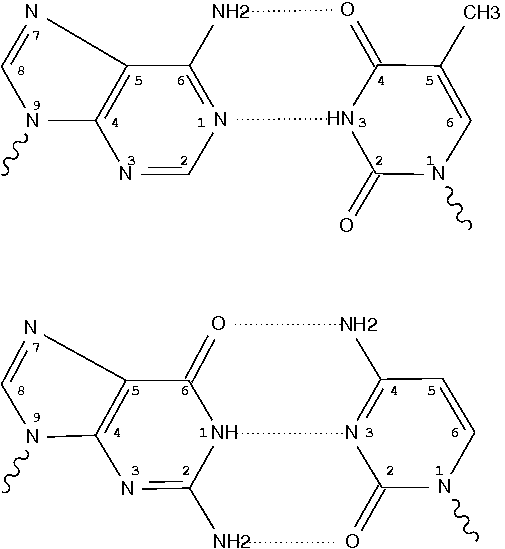

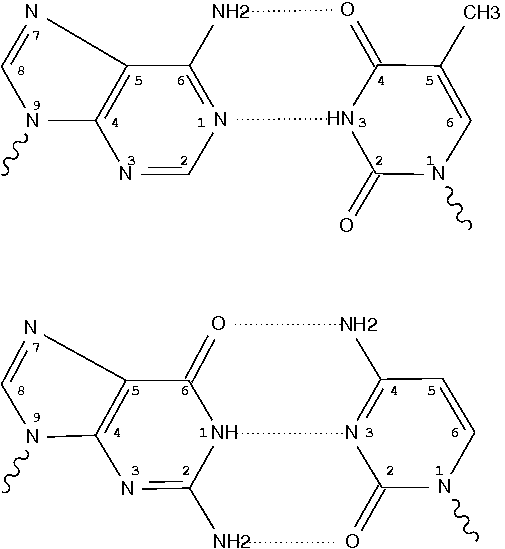

By following DSSR citations, I recently came across the paper by Saon et al. (2025), titled 'Identification and characterization of shifted G•U wobble pairs resulting from alternative protonation of RNA.' This paper provides a detailed analysis of shifted G-U wobble pairs in RNA, characterized by the opposite positioning of G vs. U in the standard G-U wobble pair (see figure below). Conventionally, a G-U wobble has the U located in the major groove, whereas a shifted G-U wobble has the G located in the major groove.

Specifically, the shifted G-U wobble pair involves an H-bond between the N2(G) and N3(U) atoms, which would be donor-donor if U were in its neutral form. There are three ways to rationalize the formation of this H-bond: (1) anionic U as originally proposed by Westhof et al. (2023), (2) U-enolate, and (3) G-imino tautomeric forms as illustrated by Saon et al. (2025). Since the position of the H-atoms cannot be determined from X-ray diffraction and cryo-EM structures, it is not possible (in my understanding) to determine which of these three mechanisms is correct—perhaps it involves a combination of them. What is clear is that the shifted G-U wobble pair is supported by strong experimental evidence from diverse sources. The authors identified 373 high-confidence shifted G-U wobble pairs across four separate structural clusters, spanning all three domains of life.

Structure of standard and shifted G-U wobble pairs. The examples are taken from PDB entry 8B0X (Fromm et al., 2023) and generated using DSSR and PyMOL. Atom names in the Watson-Crick edges are shown in red and blue for oxygen and nitrogen, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines in magenta. The unusual N2(G)...N3(U) hydrogen bond is marked with a star; it would be donor-donor if U were in its neutral form. The shaded illustration at the bottom is taken from Saon et al., showing shifted G-U wobble pairs in anionic, U-enolate, and G-imino tautomeric forms.

Structure of standard and shifted G-U wobble pairs. The examples are taken from PDB entry 8B0X (Fromm et al., 2023) and generated using DSSR and PyMOL. Atom names in the Watson-Crick edges are shown in red and blue for oxygen and nitrogen, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines in magenta. The unusual N2(G)...N3(U) hydrogen bond is marked with a star; it would be donor-donor if U were in its neutral form. The shaded illustration at the bottom is taken from Saon et al., showing shifted G-U wobble pairs in anionic, U-enolate, and G-imino tautomeric forms.

I'm glad to see that DSSR has been used in the analysis, as shown in the following excerpts from the paper.

The selected structures were then characterized by Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA (DSSR) software [34]. This step output base pair, hydrogen bond, stacking, glycosidic angle, and sugar pucker information for each structure file.

From the DSSR base pair information, all G•U base pairs were identified and filtered as wobble or non-wobble base pairs. All base pairs called by DSSR as G•U wobbles were considered for the next steps of the analysis as standard wobbles. Any base pairs containing hydrogen bonds between G(N1) and U(O4), as well as G(N2) and U(N3) (see Fig. 1) were binned to shifted wobble base pairs.

From the base pair information extracted from the DSSR characterization output, the non-redundant G•U wobbles were binned based on their location in one of the five secondary structure motifs: (1) inside stem, with one WCF base pair above and one below, (2) terminal, with at least one WCF base pair above, (3) terminal, with at least one WCF base pair below, (4) unstructured, where no WCF base pair is right above or below and the wobble does not occur at the closing base pair of a hairpin loop with a maximum of 10 nucleotides, and (5) inside a loop.

Next, for each of the five members, we retrieved the 3D structure of the 20 residues from the respective pdb files and obtained the underlying secondary structures for each of the five files in dot bracket notation using DSSR [34].

DSSR implements a geometric approach to identify hydrogen bonds, including unconventional donor/acceptor combinations (e.g., the N3-to-N3 hydrogen bond in the hemiprotonated cytosine–cytosine base pair in the i-motif). It is capable of identifying all pairs that actually exist in a given structure, whether they are canonical (Watson-Crick or G-U wobble) or non-canonical. The latter pairs may include normal or modified nucleotides, regardless of their tautomeric or protonation state.

Thus, DSSR detects standard G-U wobble pairs and names them as such ('Wobble'). Moreover, it also detects shifted G-U wobble pairs and previously named them as '~Wobble,' meaning similar to a standard wobble pair. Note that the '~Wobble' designation is based on the geometric approach of DSSR, which involves the cW-W relative orientation of the two bases and a large shear value. It is not limited to wobble pairs between G and U.

After reading the Saon et al. paper, I have revised DSSR to specifically characterize shifted G-U wobble pairs and named them as 'sWobble.' The term 'shifted-Wobble' would be too long for the DSSR text output, and using 's' also reflects the shear parameter, which is key in characterizing wobble pairs. As a concrete example, the following DSSR command

x3dna-dssr -i=8B0X.cif --pair-only --more -o=8B0X-pairs.out

would generate the below output in the file 8B0X-pairs.out. Note the name sWobble, the hydrogen bond N3(imino)*N2(amino)[3.26] with a * to indicate an unusual donor/acceptor combination, and the -2.33 shear value.

607 A.U1086 A.G1099 U-G sWobble -- cWW cW-W

[-171.2(anti) ~C3'-endo lambda=33.9] [-170.0(anti) ~C3'-endo lambda=59.2]

d(C1'-C1')=11.57 d(N1-N9)=9.60 d(C6-C8)=10.07 tor(C1'-N1-N9-C1')=8.8

H-bonds[2]: "N3(imino)*N2(amino)[3.26],O4(carbonyl)-N1(imino)[2.64]"

interBase-angle=26 Simple-bpParams: Shear=-2.23 Stretch=0.69 Buckle=22.1 Propeller=-13.8

bp-pars: [-2.33 0.13 -0.80 24.83 -7.98 -20.38]

The new DSSR version can automatically detect all 373 high-confidence shifted G-U wobble pairs listed in Table S3 of the Saon et al. paper. It will be released soon. This is yet another example of how DSSR is being actively improved to better serve the research community.

References

- Saon,M.S. et al. (2025) Identification and characterization of shifted G•U wobble pairs resulting from alternative protonation of RNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 53, gkaf575.

- Westhof,E. et al. (2023) Anionic G•U pairs in bacterial ribosomal rRNAs. RNA, 29, 1069–1076.

- Fromm,S.A. et al. (2023) The translating bacterial ribosome at 1.55 Å resolution generated by cryo-EM imaging services. Nat Commun, 14, 1095.

As of v2.5.4-2025jun06, DSSR automatically checks for steric clashes or exact duplicates of residues in an input coordinate file. It reports such issues instead of crashing, and will terminate only if an excessive number of overlaps are detected. An simplified example is shown below, which contains two nucleotides (G#1) on chains 0 and 1, respectively

ATOM 1 OP3 G 0 1 -4.270 51.892 37.186 1.00 27.93 O

ATOM 2 P G 0 1 -3.834 50.887 37.436 1.00 28.61 P

ATOM 3 OP1 G 0 1 -4.601 49.700 37.549 1.00 27.02 O

ATOM 4 OP2 G 0 1 -4.061 52.011 36.684 1.00 25.80 O

ATOM 5 O5' G 0 1 -2.906 51.105 38.691 1.00 28.01 O

ATOM 6 C5' G 0 1 -1.941 52.126 38.781 1.00 26.76 C

ATOM 7 C4' G 0 1 -1.037 51.914 39.967 1.00 26.12 C

ATOM 8 O4' G 0 1 -1.822 51.894 41.184 1.00 24.21 O

ATOM 9 C3' G 0 1 -0.285 50.591 39.988 1.00 25.12 C

ATOM 10 O3' G 0 1 0.884 50.614 39.172 1.00 26.09 O

ATOM 11 C2' G 0 1 0.008 50.411 41.462 1.00 26.05 C

ATOM 12 O2' G 0 1 1.102 51.209 41.880 1.00 27.46 O

ATOM 13 C1' G 0 1 -1.271 50.952 42.083 1.00 28.40 C

ATOM 14 N9 G 0 1 -2.272 49.904 42.329 1.00 27.27 N

ATOM 15 C8 G 0 1 -3.470 49.733 41.686 1.00 26.55 C

ATOM 16 N7 G 0 1 -4.137 48.712 42.125 1.00 25.36 N

ATOM 17 C5 G 0 1 -3.332 48.176 43.118 1.00 25.64 C

ATOM 18 C6 G 0 1 -3.529 47.056 43.955 1.00 24.98 C

ATOM 19 O6 G 0 1 -4.492 46.284 43.991 1.00 24.56 O

ATOM 20 N1 G 0 1 -2.460 46.862 44.821 1.00 24.78 N

ATOM 21 C2 G 0 1 -1.346 47.639 44.878 1.00 24.96 C

ATOM 22 N2 G 0 1 -0.417 47.298 45.782 1.00 23.72 N

ATOM 23 N3 G 0 1 -1.145 48.689 44.109 1.00 25.74 N

ATOM 24 C4 G 0 1 -2.171 48.901 43.257 1.00 26.32 C

ATOM 1 OP3 G 1 1 -6.437 51.060 40.254 1.00 27.81 O

ATOM 2 P G 1 1 -5.327 50.209 39.884 1.00 28.55 P

ATOM 3 OP1 G 1 1 -5.668 48.792 39.652 1.00 26.90 O

ATOM 4 OP2 G 1 1 -4.838 51.036 38.808 1.00 25.57 O

ATOM 5 O5' G 1 1 -4.301 50.297 41.090 1.00 27.94 O

ATOM 6 C5' G 1 1 -3.427 51.393 41.257 1.00 26.67 C

ATOM 7 C4' G 1 1 -2.528 51.168 42.443 1.00 26.12 C

ATOM 8 O4' G 1 1 -3.335 50.964 43.624 1.00 24.16 O

ATOM 9 C3' G 1 1 -1.648 49.928 42.372 1.00 25.13 C

ATOM 10 O3' G 1 1 -0.467 50.136 41.599 1.00 26.15 O

ATOM 11 C2' G 1 1 -1.372 49.649 43.835 1.00 25.96 C

ATOM 12 O2' G 1 1 -0.375 50.515 44.354 1.00 27.37 O

ATOM 13 C1' G 1 1 -2.714 50.006 44.458 1.00 28.21 C

ATOM 14 N9 G 1 1 -3.608 48.845 44.581 1.00 27.06 N

ATOM 15 C8 G 1 1 -4.771 48.614 43.895 1.00 26.37 C

ATOM 16 N7 G 1 1 -5.340 47.496 44.226 1.00 25.18 N

ATOM 17 C5 G 1 1 -4.502 46.957 45.190 1.00 25.44 C

ATOM 18 C6 G 1 1 -4.599 45.755 45.923 1.00 24.77 C

ATOM 19 O6 G 1 1 -5.480 44.892 45.864 1.00 24.39 O

ATOM 20 N1 G 1 1 -3.532 45.594 46.796 1.00 24.63 N

ATOM 21 C2 G 1 1 -2.504 46.469 46.949 1.00 24.81 C

ATOM 22 N2 G 1 1 -1.560 46.145 47.845 1.00 23.58 N

ATOM 23 N3 G 1 1 -2.396 47.594 46.280 1.00 25.56 N

ATOM 24 C4 G 1 1 -3.422 47.779 45.423 1.00 26.12 C

Running DSSR on the above coordinates will show the following output:

[i] 0.G1 and 1.G1 in clashes: min_dist=0.57

where min_dist refers to the minimum distance between heavy atoms of the two nucleotides.

The clash-detection feature in DSSR was added in response to the bioRxiv preprint by Kretsch et al. (2025), titled "Assessment of nucleic acid structure prediction in CASP16" (https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.06.652459), which noted that in some predicted RNA models submitted to CASP16, multiple models were not properly delineated with MODEL/ENDMDL in PDB format or _atom_site.pdbx_PDB_model_num in mmCIF format. I communicated with the authors, who kindly provided the PDB files to help debug the issue. For more details, see the blog post Improving DSSR through extreme cases from early June 2025 at https://home.x3dna.org/highlights/improving-dssr-through-extreme-cases.

The bioRxiv paper by Kretsch et al. was recently published in Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. The relevant citation to DSSR is in Section 2.8 | Secondary Structure Analysis, as follows:

Secondary structures were extracted from CASP16 models with DSSR (v1.9.9-2020feb06) [47]. Some models, in particular due to large clashes, could not be processed by DSSR (Table S1). The base-pair list was extracted from the table in the output file directly because the dot-bracket structure produced by DSSR, in particular for multimers, contained errors. The canonical base pairs were defined as those labeled as Watson-Crick-Franklin (WC) and wobble base pairs (hereafter referred to as ‘base pairs’ or ‘pairs’). All other base pairs are defined as non-canonical base pairs and analyzed separately. Crossed base pairs (pseudoknots) were defined as non-nested canonical base pairs, that is, any canonical base pair (i,j) for which another canonical base pair (k,l) existed with i < k < j < l or k < i < l < j. Singlet base pairs were defined as any canonical base pair that was not part of a stem, that is, (i,j) such that there was no neighboring canonical base pair between i + 1 and j − 1 or between i − 1 and j + 1. Intermolecular base pairs were identified as any canonical base pair between nucleotides in different chains.

It is worth noting that DSSR is actively supported, and I always strive to respond to users’ questions via email or (preferably) on the 3DNA Forum quickly and concretely. If you have any questions about DSSR or need clarifications, please feel free to contact me. Additionally, I monitor 3DNA/DSSR citations in the literature and proactively address issues that come to my attention when necessary.

I recently came across the paper by Zurkowski et al. (2025), titled "Detecting polynucleotide motifs: Pentads, hexads, and beyond.". The authors introduce LinkTetrado, a software tool that is described as "the first fully automated method for detecting polyadic motifs in the three-dimensional structures of nucleic acids." I am somewhat surprised by this claim, as I believe it overlooks the 2015 DSSR paper, which includes a dedicated section on "Higher-order coplanar base associations (multiplets)" as shown below:

DSSR defines multiplets as three or more bases associated in a coplanar geometry via a network of hydrogen-bonding interactions. Multiplets are identified through inter-connected base pairs, filtered by pair-wise stacking interactions and vertical separations to ensure overall coplanarity (Supplementary Figures S1, S3, S4 and S7). The abundant A-minor motifs (33) (types I and II, Supplementary Figures S3, S4 and S7) are base triplets, the smallest multiplet. The G-tetrad motif, where four guanines are associated via four pairs in a square planar geometry, is another special case of a multiplet.

In fact, DSSR multiplets are all-encompassing, including pentads, hexads, heptads, octads, etc.

The DSSR User Manual has extensive discussions (see Section 3.2.4 "Multiplets (higher-order coplanar base associations)") and several examples of multiplets, including:

- Figure 8: The GUA triplet auto-identified by DSSR in PDB entry 1msy.

- Figure 12: Base pentad (AUAAG) auto-identified by DSSR in PDB entry 1jj2. The five nts (A306,U325,A331,A340,G345) are all within the 23S rRNA.

DSSR can successfully identify the multiplets reported in the Zurkowski et al. paper, although there may be minor differences due to variations in cutoffs and definitions. For instance, using PDB ID 6w9p (shown in Fig. 7F of the Zurkowski et al. paper), DSSR can perform the following:

x3dna-dssr -i=6w9p.pdb -o=6w9p.out

x3dna-dssr -i=dssr-multiplets.pdb --select-model=4 -o=G4T3.pdb

The relevant portions of DSSR output (6w9p.out) are shown below:

List of 4 multiplets

1 nts=4 GGGG A.DG4,A.DG10,A.DG16,A.DG22

2 nts=4 GGGG A.DG5,A.DG11,A.DG17,A.DG23

3 nts=4 GGGG A.DG7,A.DG13,A.DG19,A.DG25

4 nts=7 GTGTGTG A.DG6,A.DT9,A.DG12,A.DT15,A.DG18,A.DT21,A.DG24

...

2 dssr-multiplets.pdb -- an ensemble of multiplets

DSSR can further render the extracted G4T3.pdb into the following image using PyMOL:

DSSR has far more to offer than meets the eye. See the DSSR User Manual and the practical guide to DSSR-PyMOL integration for more details.

References

Lu,X.-J. et al. (2015) DSSR: an integrated software tool for dissecting the spatial structure of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res, gkv716.

Zurkowski,M. et al. (2025) Detecting polynucleotide motifs: Pentads, hexads, and beyond. PLoS Comput Biol, 21, e1013633.

Recently, I noticed that a user had uploaded a file to the website "DSSR-enabled Innovative Schematics of 3D Nucleic Acid Structures with PyMOL", which DSSR reported as 'no nucleotides found.' Upon visualizing it in PyMOL, the structure appeared to be a single-stranded RNA. Further investigation revealed that while the uploaded file was in PDB format, it did not adhere to the standard naming conventions for nucleotides typically used in RCSB PDB entries. For instance, an A nucleotide extracted from the file had its exocyclic amino group named as N553 instead of the conventional N6 (see below).

Following 3DNA, DSSR uses the atomic coordinates and standard names of base-ring atoms to identify a nucleotide. All known nucleotides share a common six-membered pyrimidine ring, with atoms named consecutively (N1, C2, N3, C4, C5, C6), and purines include three additional atoms (N7, C8, N9). See below for the standard names in Watson-Crick base pairs.

Without proper names for base ring atoms, DSSR is unable to identify nucleotides, resulting in the input structure being reported as 'no nucleotides found.' The same principle applies to amino acids in protein structures, such as specific naming conventions for amino nitrogen (N), carbonyl carbon (C), and alpha carbon (CA).

See also the blog posts "Mapping of modified nucleotides in DSSR" and "Name of base atoms in PDB formats".

By following DSSR citations, I recently noticed a bioRxiv preprint, titled "Assessment of nucleic acid structure prediction in CASP16" by Kretsch et al. The portion where DSSR is mentioned is as follows:

Secondary structures were extracted from CASP16 models with DSSR (v1.9.9-2020feb06). Some models, in particular due to large clashes, failed to run (Supplemental Table 1). The base-pair list was extracted from the table in the output file directly because the dot-bracket structure produced by DSSR, in particular for multimers, can contain errors.

While pleased to see DSSR cited in this significant study, I am concerned about the reported issues and would like to investigate the specific structures and error messages encountered. To better understand the problems and potentially find solutions, I have reached out to the authors for further details. Here is the message I sent initially:

You said DSSR failed to run on some models with large clashes. Could you please share the specific models and the error messages you encountered? I would also be interested in seeing the exact errors you observed in the DSSR-derived DBN for multi-mers. It would be a great opportunity for me to improve DSSR in this area, which would benefit both your group and the broader community. If you are willing to share them, please provide details—preferably on the **public 3DNA Forum**. Don’t hesitate to share openly any bugs or limitations you’ve encountered with DSSR.

The authors responded promptly and provided detailed information about the specific models and error messages encountered. After several

iterations, I successfully resolved the issues and released an updated version of DSSR, namely v2.5.4-2025jun04. You can find the release notes

here. This experience underscores the importance of proactively engaging with the community to enhance the functionality and reliability of a software tool.

In this blog post, I aim to share the specifics of these issues and the steps taken to address them. For ease of reading, I have formatted the response/feedback from the authors in red block quotes, and my enquiries/comments in blue. The beginning round of correspondence is as below.

Do note, the predictors in casp submit some truly atrocious models --- eg 14 atoms all at the exact same x-y-z coordinate. These errors would be with his v1.9.9-2020feb06 install though not your latest version. Would you still like them?

Yes, I would like to see how DSSR behaves with these models. Ideally, it should not crash, but output some warning messages. Only through such testing can we improve the robustness of DSSR. Overall, the more feedback I get, the better.

Buffer overflow bug in DSSR

Most of errors I had with dssr were due to clashes and all zero xyz predictions by predictors, for all of which dssr did not give an error message when dssr failed. There was a case where the prediction looked reasonable but dssr failed with the error message `dssr error*** buffer overflow detected ***`. Please see attached for the 2 pdbs that gave this error.

The two PDB files I received were R1283v3TS294_1o and R1283v3TS294_2o, as listed in Supplementary Table 1: "List of unscored models," with the "Reasons" column indicating a dssr error*** buffer overflow detected ***. I immediately acknowledged receipt of these files, as shown in the following message:

Thank you for sending me the two PDB files which caused DSSR to fail. I can verify the issue and will try to fix the bug ASAP. I'll keep you posted.

Using these data files, I was able to quickly fix the buffer overflow bug. The following is my response to the authors within one day after receiving the files:

With your sample PDB files, I have traced the issue that caused DSSR to fail. The bug was due to a 53-way (`R1283v3TS294_1o`) and 40-way (`R1283v3TS294_2o`) junction loops which are far from the norm. DSSR sets a default limit for the summary line for each loop which is more than sufficient for all normal PDB entries, but falls short for these unusual cases, leading to out of array boundaries. See the attached DSSR output after the bug fix for more details.

This is a clear example where user feedback is crucial for improving the software, which makes it better serve the community.

Zero xyz coordinates and large clashes

After fixing the out-of-bound bug, I also requested other problematic predicted models from the authors, as shown in the following message:

Along the line, please provide the sample PDB files:

- with zero xyz predictions -- I am curious to see what it looks like.

- where the DSSR-derived DBN is problematic for multi-mers

After solving these issues, I will release a new version of DSSR that would make your analysis more straightforward, and benefit other users as well.

The authors responded with the following message:

Thanks for looking into this. Here are some more examples with superimposed structures, large clash, and all zero xyzs in the zip file.

The ZIP file (error_examples.zip) contains three folders (all_zero_xyz, clash and superimposed), each with some problematic models in PDB format. Once again, I promptly acknowledged receipt of the files and was able to reproduce the reported issues.

Garbage in, garbage out. Given these problematic models, one should not expect DSSR to extract any meaningful information from them. Nonetheless, I am committed to enhancing the software so that it can handle such cases more effectively by providing clear error messages and terminating gracefully rather than crashing.

After several days of thinking, elaboration, intensive coding, and testing, I solved the problems. I then communicated the results to the authors in the following detailed message:

Thanks for the sample PDB files (`error_examples`) with all zero XYZ coordinates, large clashes, and superimposed structures. They helped me to understand the issues, think in context, and find solutions. Let's look them one by one:

1. `all_zero_xyz`: These two files `R1211TS159_1` and `R1211TS159_2` have identical contents, except for the MODEL IDs (1 and 2, respectively). Atoms with all-zero XYZ coordinates are a special case of duplicated coordinates. This has led me to implement a check for duplicated coordinates in an input file. The revised DSSR now reports duplicated coordinates and their corresponding atoms, and it quits if the number of duplicated atoms exceeds a certain threshold. For `R1211TS159_1`, the revised DSSR output would be as below:

1 [e] xyz repeated 1904 times:[0.000 0.000 0.000] 1509-P@0.G1 3412-C6@0.C90

[w] no-of-repeats=1 max-freq=1904

...too many duplicates... quit!

2. `clash`: Both files `R1250TS208_1o` and `R1250TS417_1o` contain multiple models, as visible in PyMOL. Each PDB file uses a single MODEL/END pair to include all its models. This setup is akin to an NMR ensemble but without MODEL/ENDMDL delimiters, which leads to clashes when analyzed together. I have revised DSSR to explicitly check for such clashes and terminate execution if too many are detected. Using `R1250TS208_1o` as an example, the DSSR output would be as below:

[i] 0.G1 and 1.G1 in clashes: min_dist=0.57

[i] 0.G1 and 3.G1 in clashes: min_dist=0.35

[i] 0.G1 and 4.G1 in clashes: min_dist=0.41

...too many clashes... quit!

The above list contains only three of the many clashes detected in this file. One can notice immediately the G1 nucleotides from chains `0`, `1`, `3`, and `4` are in clashes (see the attached file `clashes_208.pdb`, which contains only G1 nucleotides from the four chains).

3. `superimposed`: The five example files (`R1283v3TS304_1o` ... `R1283v3TS304_5o`) have similar issues as the clash cases. Running the revised DSSR on `R1283v3TS304_1o` would produce the following output:

[i] 0.A1 and 2.A1 in clashes: min_dist=0.74

[i] 0.A1 and 3.A1 in clashes: min_dist=0.78

[i] 0.A1 and 4.A1 in clashes: min_dist=0.56

...too many clashes... quit!

Here A1 nucleotides from chains `0`, `2`, `3` , and `4` are in clashes (see the attached `superimpose-1.pdb`).

How the `clash` and `superimposed` categories are supposed to be different? They look similar to me.

Overall, the `error_examples` (in `all_zero_xyz`, `clash`, and `superimposed`) pose problems because they do not contain valid DNA/RNA structures as a whole. DSSR cannot extract meaningful information from these files. However, the revised DSSR explicitly highlights these issues, saving users from spending time on invalid data. Do these DSSR revisions make sense to you?

In the end, I am glad to receive the following feedback from the authors:

Thanks, these revisions all make sense! The examples I sent on clashes and superimposed were actually similar and I think the error output makes sense as well.

Final thoughts

This blog post offers an in-depth look at my efforts to enhance DSSR. As the developer of this software product, I am deeply committed to ensuring its quality and usability. I extend my gratitude to the authors for their valuable feedback and assistance in resolving these issues. In return, the updated version of DSSR (v2.5.4-2025jun04) should not only streamline their workflow but also benefit the broader user community.

For those who read through this lengthy post, I want to emphasize that DSSR is actively supported: I am here to listen and help. Any questions related to its use, bug reports, or feature requests are warmly welcomed on the 3DNA Forum. As I’ve mentioned before, please don’t hesitate to share any negative experiences or bugs with DSSR—just ensure to provide specific details so others can reproduce the issue. I will address these concerns as soon as I’m aware of them and will frankly acknowledge any mistakes I may have made. My goal is for DSSR to be a reliable software tool that the community can trust and build upon.

References

Kretsch,R.C. et al. (2025) Assessment of nucleic acid structure prediction in CASP16. bioRxiv; https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.06.652459.

In DSSR, the --frame option allows users to reorient a nucleic acid structure using the standard base reference frame (see Olson et al., 2001). This option can be applied not only to an individual base frame but also a base-pair frame, or the middle frame between two bases or base pairs. These variations facilitate the alignment of nucleic acid structures for a wide range of comparative analyses. In this blog post, I will demonstrate how to use the --frame option with concrete examples, enabling readers to apply this unique DSSR feature to their own projects.

The standard base reference frame

The standard base reference frame is derived from an idealized Watson-Crick base pairing geometry (top-left, figure below). The x-axis points in the direction of the major groove along what would be its pseudo-dyad axis—that is, the perpendicular bisector of the C1'...C1' vector spanning the base pair. The y-axis runs along the long axis of the idealized base-pair in the direction of the sequence strand, parallel to the C1'...C1' vector, and is displaced so as to pass through the intersection between the (pseudo-dyad) x-axis and the vector connecting the pyrimidine Y(C6) and purine R(C8) atoms. The z-axis is defined by the right-handed rule. For right-handed A- and B-DNA, the z-axis accordingly points along the 5' to 3' direction of the sequence strand.

Typical usages of the --frame option

Using the classic B-DNA dodecamer PDB entry 355d as an example, DSSR can be run with the --frame option as follows:

# 1...5..8....

# chain A: 5'-CGCGAATTCGCG -3'

# chain B: 3'-GCGCTTAAGCGC -5'

# reorient 355d in the reference frame of C1 on chain A

x3dna-dssr -i=355d.pdb --frame=A.1 -o=355d-b1.pdb

# reorient 355d in the frame of the Watson-Crick pair C1-G24

x3dna-dssr -i=355d.pdb --frame=A.1:wc -o=355d-bp1.pdb

# ... with the minor-groove of pair C1-G24 facing the viewer

x3dna-dssr -i=355d.pdb --frame=A.1:wc-minor -o=355d-bp1-minor.pdb

# with the minor-groove of the middle AATT tract facing the viewer

x3dna-dssr -i=355d.pdb --frame='A.5:wc-minor A.8:wc' -o=355d-AATT-minor.pdb

# Rendered in cartoon-blocks with base-pair blocks, and black minor-groove

# Load 355d-AATT-minor.pml into PyMOL (bottom-left, figure above)

x3dna-dssr -i=355d-AATT-minor.pdb --cartoon-block --block-file=wc-minor -o=355d-AATT-minor.pml

The abbreviated notation A.1 refers to nucleotide numbered 1 (as indicated in the coordinates file) on chain A. Here, it denotes C1, as shown at the top of the listing. Similarly, A.5 and A.8 correspond to nucleotides A5 and T8 on chain A, respectively. In most cases, such as with 355d, the combination of chain identifier and residue number is sufficient to uniquely identify a nucleotide. More generally, other information such as model number or insertion code may be needed to specify a particular nucleotide.

In the above listing, wc after the colon (for example, A.1:wc) specifies the Watson-Crick base pair that the corresponding nucleotide participates in. Meanwhile, minor transforms the structure so that the minor-groove of the base (or base pair, or step) faces the viewer. The keywords wc and minor are settings that influence the construction or view of the frame. Case or order does not matter for these keywords as long as there is a match—for example, minor+wc works the same as wc-minor.

Two other examples combining the --frame option with cartoon-block representations

The intuitive geometric meaning of the standard base reference frame combined with the DSSR-enabled cartoon-block representation allows for an enhanced understanding of intricate structural features. In the top-right panel of the figure above, we see the classic yeast phenylalanine tRNA (PDB entry 1ehz) viewed into the minor-groove of the pseudo-knotted G19-C56 pair at the elbow of the L-shaped tertiary structure. The stacking interactions of the purines at the top-right of the panel are clearly visible in this view. In the bottom-right panel, an anti-parallel G-quadruplex from PDB entry 8ht7 is shown. The G-tetrads are automatically identified and rendered as square blocks, all with DSSR. This representation makes the chair conformation of the three-layered anti-parallel G-quadruplex crystal clear. The DSSR commands used are listed below:

# yeast tRNA (1ehz)

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --frame=A.19:wc-minor -o=1ehz-elbow.pdb

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz-elbow.pdb --cartoon-block --block-file=wc-minor -o=1ehz-elbow.pml

# anti-parallel chair-shaped G-quadruplex (8ht7)

x3dna-dssr -i=8ht7.pdb --select=nts -o=8ht7-nts.pdb # extract nucleotides, ignore amino acids

# reorient 8ht7 in the frame of the G-tetrad involving G1, in edge view

x3dna-dssr -i=8ht7-nts.pdb --frame=A.1:G4-minor -o=8ht7-Gtetrad.pdb

x3dna-dssr -i=8ht7-Gtetrad.pdb --block-cartoon --block-file=G4-minor -o=8ht7-Gtetrad.pml

References

Olson,W.K. et al. (2001) A standard reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry. Journal of Molecular Biology, 313, 229–237.

The 3DNA suite includes the mutate_bases program, which, as its name suggests, mutates bases while maintaining the backbone conformation. This feature was incorporated into the suite following user feedback and has been utilized in several studies before being formally published in the Li et al. (2019) paper. A key advantage is that the mutation process preserves both the geometry of the sugar-phosphate backbone and the base reference frame, encompassing position and orientation. Consequently, re-analyzing the mutated model yields identical base-pair and step

parameters as those of the original structure.

In DSSR, the standalone mutate_bases program has become the mutate sub-command with enhanced functionality and improved usability, as documented in the User Manual. The mutate module allows users to perform base mutations efficiently and effectively by taking advantage of the powerful DSSR analysis engine.

To further expand the modeling capabilities of the DSSR, v2.5.3 introduced the --mutate-type option to allow for backbone mutations, based on the base reference frame. Furthermore, the target can be any fragment, regardless of length or composition, rather than just a single nucleotide. When combined with the rebuild module, this feature significantly enhances DSSR’s ability to model nucleic acid structures.

Here is an example of modeling PDB entry 1msy, a 27-nt structure (1msy.pdb) that mimics the sarcin/ricin loop from E. coli 23S ribosomal RNA.

x3dna-dssr analyze -i=1msy.pdb --ss --rebuild -o=1msy-expt.out

mv dssr-ssStepPars.txt 1msy-step.txt

x3dna-dssr rebuild --backbone=RNA --par-file=1msy-step.txt -o=1msy-step.pdb

x3dna-dssr -i=1msy.pdb --select-resi='A 2654' -o=1msy-A2654.pdb

x3dna-dssr -i=1msy.pdb --select-resi='A 2655' -o=1msy-G2655.pdb

x3dna-dssr -i=1msy-A2654.pdb --frame=2654 -o=frame___A.pdb

x3dna-dssr -i=1msy-G2655.pdb --frame=2655 -o=frame___G.pdb

x3dna-dssr mutate -i=1msy-step.pdb --entry='num=8 to=A; num=9 to=G' -o=1msy-C2endo.pdb --mutate-part=whole

x3dna-dssr --connect-file -i=1msy-C2endo.pdb -o=1msy-C2endo-cnt.pdb --po-bond=5.0

- The

analyze step uses options --ss and --rebuild to generate the file dssr-ssStepPars.txt (containing base-step parameters), which is then renamed to 1msy-step.txt. The rebuild step employs 1msy-step.txt to construct a structure (1msy-step.pdb) with regular C3'-endo sugar RNA backbone conformation. Note that the rebuilt structure has nucleotides numbered from 1 to 27, while in the PDB 1msy, they correspond to 2647 to 2673, respectively.

- However, the A2654 and G2655 dinucleotides in 1msy are actually in C2'-endo sugar conformation, creating the S-shaped structure around the GpU platform. The above rebuilt structure does not reflect this distortion. So we extract A2654 and G2655 with

--select-resi and then put each in its standard base reference frame, named frame___A.pdb and frame___G.pdb, respectively.

- Now we mutate A8 and G9 in the rebuilt structure

1msy-step.pdb to A and G with option --mutate-part=backbone to ensure the backbone conformations are changed according to those in frame___A.pdb and frame___G.pdb, respectively. The resulting structure is named 1msy-C2endo.pdb. Now the S-shape around the GpU platform is preserved, even though the backbone are not always covalently connected, due to large O3'(i-1) to P(i) distances between neighboring nucleotides. The last step is to generate CONECT records with --connect-file option to connect the backbone atoms explicitly, resulting in more smooth backbone cartoon representation in PyMOL as shown below.

As noted in the Li et al. (2019) paper, users can optimize this approximate backbone connection using Phenix, while keeping the base atoms fixed. The 3DNA-Phenix combination leads to a model where the base geometry strictly follows the parameters prescribed in the user-specified file, and the backbone is regularized with improved stereochemistry and a ‘smooth’ appearance in ribbon representation.

There are other variants of the DSSR mutate module, including for building Z-DNA backbones. However, the above example is sufficient to demonstrate the power of the integrated approach enabled by DSSR for the analysis and modeling of nucleic acid structures. See the DSSR User Manual for more details.

References

Li,S. et al. (2019) Web 3DNA 2.0 for the analysis, visualization, and modeling of 3D nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res., 47, W26–W34.

The default human-readable output file,

The default human-readable output file,  Structure of standard and shifted G-U wobble pairs. The examples are taken from PDB entry 8B0X (Fromm et al., 2023) and generated using DSSR and PyMOL. Atom names in the Watson-Crick edges are shown in red and blue for oxygen and nitrogen, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines in magenta. The unusual N2(G)...N3(U) hydrogen bond is marked with a star; it would be donor-donor if U were in its neutral form. The shaded illustration at the bottom is taken from Saon et al., showing shifted G-U wobble pairs in anionic, U-enolate, and G-imino tautomeric forms.

Structure of standard and shifted G-U wobble pairs. The examples are taken from PDB entry 8B0X (Fromm et al., 2023) and generated using DSSR and PyMOL. Atom names in the Watson-Crick edges are shown in red and blue for oxygen and nitrogen, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines in magenta. The unusual N2(G)...N3(U) hydrogen bond is marked with a star; it would be donor-donor if U were in its neutral form. The shaded illustration at the bottom is taken from Saon et al., showing shifted G-U wobble pairs in anionic, U-enolate, and G-imino tautomeric forms.