Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 stem–loop 5 (SL5) (PDB id: 9E9Q; Jones CP, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. 2025. Crystallographic and cryoEM analyses reveal SARS-CoV-2 SL5 is a mobile T-shaped four-way junction with deep pockets. RNA 31: 949–960). The T-shaped four-way junction of the coronavirus SL5 structural element provides a starting point for examining the structures of larger RNA motifs and their interactions with other molecules. Image highlighting the four arms of the junction. The RNA backbone is depicted by a gray ribbon. The bases within the arms of the junction are colored respectively in blue, red, yellow, and cyan. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for Structural Bioinformatics of Nucleic Acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

As the developer of DSSR, I am thrilled to see its application in cutting-edge research across multiple disciplines. Below is a list of four recent publications that highlight how DSSR has been utilized, underscoring its versatility and significance in structural bioinformatics.

In the Geng et al. (2025) Nucleic Acids Research (NAR) paper, titled 'Revealing hidden protonated conformational states in RNA dynamic ensembles', DSSR is simply cited as follows:

All bp geometries, hydrogen-bond, backbone, stacking, and sugar dihedral angles were calculated using X3DNA-DSSR [77].

In the preprint by Gordan et al. (2025), titled 'High-throughput characterization of transcription factors that modulate UV damage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution', DSSR is cited as follows:

Step base stacking, base pair shift, base pair slide, interbase angle, pseudorotation angle, and sugar puckering classifications of nucleobases were computed using X3DNA-DSSR (v2.5.0)75. Base stacking was defined as the overlapping polygon area in Å2 when projecting the dipyrimidine base ring atoms (excluding exocyclic atoms) into the mean base pair plane76. The sugar ring pseudorotation phase angle of each pyrimidine was also calculated using X3DNA-DSSR as described by Altona, C. & Sundaralingam, M.77 Interbase angle was defined as sqrt(propeller2+buckle2) per the X3DNA-DSSR documentation.

Figure 6: TF Binding Induces Structural Distortion Favorable to UV Dimerization is highly informative, particularly panel (a), which illustrates the ensemble of structural parameters that predispose dipyrimidines to cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD) or 6-4 pyrimidine-pyrimidones (6-4 PP) formation. DSSR is designed as an integrated software tool, offering a comprehensive suite of structural parameters not found in any other single tool I am aware of. Despite this, the innovative use of DSSR by Gordan et al. exceeds my expectations and demonstrates its versatility.

In the preprint by Kubaney et al. (2025) from the Baker group, titled 'RNA sequence design and protein-DNA specificity prediction with NA-MPNN', DSSR is cited as follows:

On the pseudoknot subset, we evaluate additional structure‐ and reactivity‐based metrics. DSSR v2.3.241 is used to extract the ground‐truth secondary structure from the native crystal structures. For each designed sequence, RibonanzaNet predicts 2A3 reactivity profiles, from which we compute predicted OpenKnot scores (see https://github.com/eternagame/OpenKnotScore)31 using the predicted reactivity together with the DSSR ground truth.

In a recent NSMB paper from the Baker group, titled 'Computational design of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins', 3DNA is cited as follows:

RIF docking of scaffolds onto DNA targets (DBP design step 1) Structures of B-DNA for each target (Supplementary Table 2) were generated by (1) using the DNA portion of PDB 1BC8 (ref. 60), PDB 1YO5 (ref. 61), PDB 1L3L (ref. 51) or PDB 2O4A (ref. 62) or (2) using the software X3DNA63, followed by a constrained Rosetta relax of the DNA structure.

Please note that 3DNA has been replaced by DSSR. The functionality for constructing B-DNA models, previously provided by 3DNA, is now directly available in DSSR via its fiber and rebuild modules.

In the preprint by Si et al. (2025), titled 'End-to-End Single-Stranded DNA Sequence Design with All-Atom Structure Reconstruction', DSSR is cited as follows:

Since ViennaRNA and NUPACK require secondary structures as input, we used DSSR35 to extract secondary structures from the corresponding ssDNA three-dimensional structures.

The above use cases are merely a sample of how DSSR is utilized in the scientific literature. It is reasonable to state that DSSR has emerged as a de facto standard tool within the field of nucleic acid structural bioinformatics. Overall, DSSR is a mature, robust, and efficient software product that is actively developed and maintained. I am committed to making DSSR synonymous with quality and value. Its unmatched functionality, usability, and support save users significant time and effort compared to alternative solutions.

DSSR is available free of charge for academic users. Additionally, it has been integrated into other high-profile bioinformatics resources, including NAKB, PDB-redo, and N•ESPript.

References

- Geng A, Roy R, Ganser L, Li L, Al-Hashimi HM. Revealing hidden protonated conformational states in RNA dynamic ensembles. Nucleic Acids Research. 2025;53:gkaf1366. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaf1366.

- Gordan R, Wasserman H, Chi B, Bohm K, Duan M, Sahay H, et al. High-throughput characterization of transcription factors that modulate UV damage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution. 2025. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-8197218/v1.

- Kubaney A, Favor A, McHugh L, Mitra R, Pecoraro R, Dauparas J, et al. RNA sequence design and protein–DNA specificity prediction with NA-MPNN. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.10.03.679414.

- Glasscock CJ, Pecoraro RJ, McHugh R, Doyle LA, Chen W, Boivin O, et al. Computational design of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2025;32:2252–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-025-01669-4.

- Si Y, Xu Y, Chen L. End-to-end single-stranded DNA sequence design with all-atom structure reconstruction. 2025. https://doi.org/10.64898/2025.12.05.692525.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve had the pleasure to talk to Thomas Holder, the PyMOL Principal Developer at Schrödinger, on possible integration of DSSR into PyMOL. On Tuesday April 21, 2015, I wrote to Thomas:

Last year, I had the please to collaborate with Dr. Robert Hanson to integrate DSSR into Jmol, see

http://chemapps.stolaf.edu/jmol/jsmol/dssr.htm. I am wondering if you have any interest in connecting DSSR to PyMOL. This will not only benefit both parties, but also bring elaborate analyses of RNA structures to the general audience. As you may be aware, RNA is becoming increasing important, yet the field of RNA structural bioinformatics is lagging (far) behind that of proteins.

After a few meet-ups, we all agree that the DSSR-PyMOL integration project would be meaningful/significant for RNA structural bioinformatics. Moreover, the community not only can benefit from the end result, but also should be able to make direct contributions through the process. On Friday May 08, 2015, Thomas sent out the following open invitation, titled Someone interested in writing a DSSR plugin for PyMOL?, to the PyMOL mailing list:

Is anyone interested in writing a DSSR plugin for PyMOL? DSSR is an integrated software tool for Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA (http://x3dna.bio.columbia.edu/docs/dssr-manual.pdf). Among other things, DSSR defines the secondary structure of RNA from 3D atomic coordinates in a way similar to DSSP does for proteins. Most of its output could be translated 1:1 into PyMOL selections, making it available for coloring and other selection based features. A PyMOL plugin could act as a wrapper which runs DSSR for an object or atom selection. Xiang-Jun Lu, the author of DSSR, is also working on base pair visualization (see http://home.x3dna.org/articles/seeing-is-understanding-as-well-as-believing), similar to (but more advanced) what’s already available from 3DNA (http://pymolwiki.org/index.php/3DNA).

Xiang-Jun would be happy to collaborate with someone who has experience with Python and the PyMOL API for writing an extension or plugin. Please contact me if this sounds appealing to you.

Get DSSR from http://home.x3dna.org/

See it hooked up with JSmol: http://chemapps.stolaf.edu/jmol/jsmol/dssr.htm

If you are self-motivated, care about software quality, have expertise in writing PyMOL plugin, and feel the pain in RNA structural analysis/visualization with currently available tools, now it is the time to make a difference. The DSSR/PyMOL project would ideally be composed of a team of dedicated practitioners with complementary skills. We will communicate mostly via email or online forum, in a presumably open and highly interactive way. By working on the project, you will be able to sharpen your skills and make new friends. The end product would not only make RNA structural bioinformatics easier for yourself but also benefit the community at large.

From the very beginning, 3DNA contains two key programs, analyze and rebuild, for the analysis and rebuilding of nucleic acid 3D structures. The two names are short and to the point, but with one caveat. They are common verbs that can be easily picked up by other software packages. When 3DNA and such packages are installed on the same machine, naming clashes happen. If the 3DNA bin/ directory is searched afterwards, the analyze or rebuild command may have nothing to do with nucleic acid structures at all. Naturally, this naming ambiguity can lead to confusions and frustrations.

I’ve been aware of the rebuild program name conflict for a long time. Recently, I was surprised by another analyze program on my Mac OS X Yosemite. As shown from the following output, the analyze program seems to be installed via Mac port, and it is about analyzing words in a dictionary file.

~ [540] which analyze

/opt/local/bin/analyze

~ [541] analyze -h

correct syntax is:

analyze affix_file dictionary_file file_of_words_to_check

use two words per line for morphological generation

The ambiguous names are exactly the reason that I use x3dna-dssr and x3dna-snap for the two new programs I’ve been working over the past few years. As for the analyze and rebuild programs in 3DNA v2.x, I’d rather leave them as is. 3DNA is now in wide use in other structural bioinformatic pipelines to allow for easy name changes without causing compatibility issues. On a positive side, once you know the problem, fixing it is straightforward. This post is to raise the awareness of the 3DNA user community about such naming conflicts.

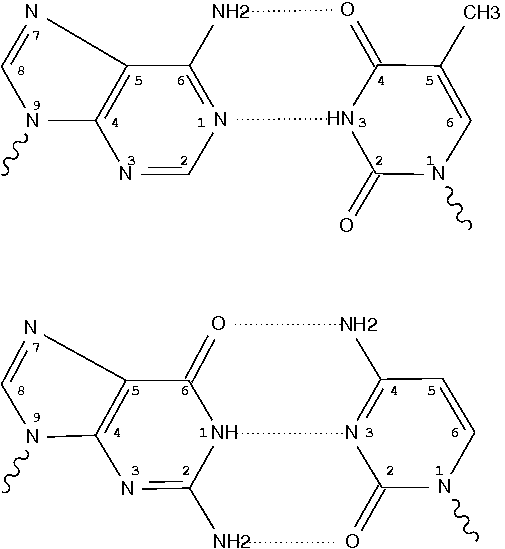

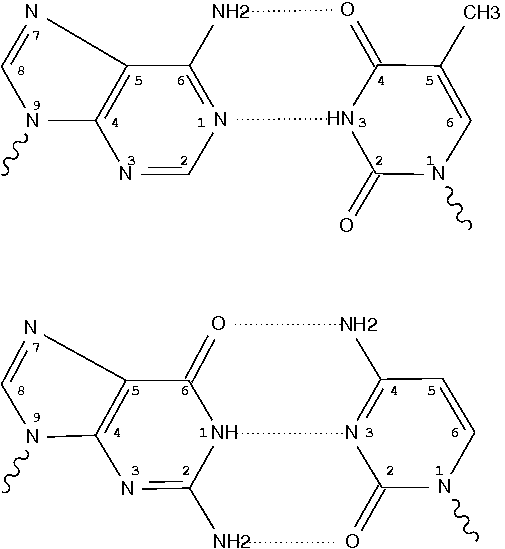

Canonical bases (A, C, G, T and U) in nucleic acid structures have standard atom names, shown below using the Watson-Crick A–T and G–C pairs. Ring atoms of adenine, for example, are named (N1, C2, N3, C4, C5, C6, N7, C8, N9) respectively.

Four characters are reserved for atom names in the PDB format. The convention, as seen in files downloaded from the RCSB PDB, is to put the two-character base name in the middle, as in .N1.. Note that here each dot (.) is used for a space character to make it stand out.

Long time ago, I became aware a PDB format variant where the base name is left-aligned, as in N1... This case has ever since been properly handled by 3DNA (including DSSR and SNAP). While checking submitted entries to web-DSSR, I recently noticed yet another PDB format variation in labeling base names with the format of ..N1 (i.e., right-aligned). Without taking this special variant of PDB format into consideration, 3DNA/DSSR reported that “no nucleotides found!” Once the issue is known, however, fixing it is straightforward. As of May 4, 2015, 3DNA v2.2, DSSR and SNAP can all handle this special PDB variant correctly.

Over the years, I have come across many PDB variants claimed to compliant with the loosely defined format. If you find 3DNA or DSSR is not working as expected, it is likely the coordinate file in the self-claimed ‘PDB format’ is at fault. Wherever practical, I’ve tried to incorporate as many non-standard variants as possible.

The NDB (Nucleic Acid Database) is a valuable resource dedicated to “information about experimentally-determined nucleic acids and complex assemblies.” Over the years, however, I’ve gradually switched from NDB to PDB (Protein Data Bank) for my research on nucleic acid structures. NDB is derived from PDB and presumably should contain all nucleic acid structures available in the PDB. However, at the time of this writing (on April 9, 2015), the NDB says: “As of 8-Apr-2015 number of released structures: 7430” and the PDB states “7611 Nucleic Acid Containing Structures”. So PDB has 7611-7430=181 more entries of nucleic acid structures than the NDB, possibly due to a lag in NDB’s processing of newly released PDB structures. Another issue is the inconsistency of the NDB identifier: early entries have e.g. bdl084 for B-DNA (355d in PDB), but now NDB seems to use the same id as the PDB (e.g., 4p5j).

The RCSB PDB maintains a weekly-updated, summary file named pdb_entry_type.txt in pure text format (check here for a list of useful summary files), containing “List of all PDB entries, identification of each as a protein, nucleic acid, or protein-nucleic acid complex and whether the structure was determined by diffraction or NMR.” An excerpt of the file is shown below:

108m prot diffraction

109d nuc diffraction

109l prot diffraction

109m prot diffraction

10gs prot diffraction

10mh prot-nuc diffraction

110d nuc diffraction

110l prot diffraction

.................................

102m prot diffraction

103d nuc NMR

Specifically, a nucleic acid structure contains the (sub)string nuc in the second field, where prot-nuc means a protein-RNA/DNA complex. This text file is trivial to parse, and the atomic coordinates files (in PDB or PDBx/mmCIF format) for all nucleic acid structures can be automatically downloaded from the RCSB PDB using a script.

It is worth noting that DSSR is checked against all nucleic acid structures in the PDB at the time of each release to ensure that it does not crash. I update my local copy of nucleic acid structures each week, and run DSSR on the new entries. This process not only provides me an opportunity to keep pace with new developments in the field but also allows me to keep refining DSSR as needs arise.

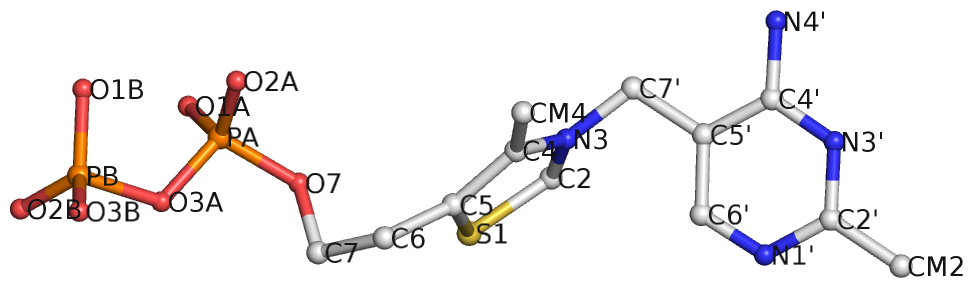

Pseudouridine (5-ribosyluracil, PSU) is the most abundant modified nucleotide in RNA. It is unique in that it has a C-glycosidic bond (C-C1′) instead of the N-glycosidic bond (N-C’) common to all other nucleotides, canonical or modified. In 3DNA, the one-letter code for PSU is assigned to the upper case ‘P’, reserving the lower case ‘p’ for its modified variants. Distinguishing PSU from standard U (or T) is important for deriving sensible base-pair parameters and the χ torsion angle.

|

|

|

| PSU |

3TD |

Recently, I came across 3TD (see figure above) in PDB entry 5afi. 3TD is a modified variant of PSU, with a methyl group attached to N3. In 3DNA v2.1 v2.1-2015mar11, 3TD is abbreviated to ‘p’ to signify its connection to PSU.

In the list of recognized nucleotides (‘baselist.dat’) distributed with 3DNA, there are two other residues mapped to ‘p’: FHU and P2U (see figure below). As is often the case, it is the chemical structure, not the 3-letter PDB ligand identifier (or even full chemical name), that shows clearly to what 3DNA 1-letter abbreviation a residue matches.

|

|

|

| FHU |

P2U |

A single-stranded RNA molecule can fold back onto itself to form various loops delineated by double helical stems, as shown in the figure below [taken from the Nearest Neighbor Database website from the Turner group].

Of special note is the exterior loop (at the bottom) which includes the 5′ and 3′ ends of the sequence. The Mfold User Manual defines the exterior loop as such:

The collection of bases and base pairs not accessible from any base pair is called the exterior (or external) loop … . It is worth noting that if we imagine adding a 0th and an (n + 1)st base to the RNA, and a base pair 0.(n+1), then the exterior loop becomes the loop closed by this imaginary base pair. … The exterior loop exists only in linear RNA.

While each of the other loops (hairpin, bulge, internal or junction) forms a closed ‘circle’ with two neighboring bases connected by either a canonical pair or backbone covalent bond, the ‘exterior loop’ has only an imaginary pair to close the 5′ and 3′ ends of the sequence. Moreover, the two ends of an RNA molecule are not necessarily close in three-dimenional space, as may be implied in the above secondary structure diagram. For example, in the H-type pseudoknotted structure 1ymo from human telomerase RNA, the 5′ and 3′ ends are on the opposite sides.

DSSR does not has the concept of an ‘exterior loop’ due to its lack of a closing pair to form a ‘circle’. Instead, each of the 5′ and 3′ dangling ends is taken as a ‘non-loop single-stranded segment’, if applicable. For the crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA (1ehz, see the figure at the bottom), the relevant portion of DSSR output is as below. Note that since the 5′ end is paired, only the single-stranded region at the 3′ end is listed. Presumably, the ‘exterior loop’ in this case would also include the G1—C72 pair, with the imaginary closing link connecting G1 and A76.

List of 1 non-loop single-stranded segment

1 nts=4 ACCA A.A73,A.C74,A.C75,A.A76

Dot bracket notation (dbn) is a popular format to represent RNA secondary structures. Initially introduced by the ViennaRNA package, dbn uses dots (.) for unpaired bases, and matched parentheses () for the canonical Watson-Crick A-T and G-C or the wobble G-U pairs. This compact representation was designed for fully nested (i.e., pseudoknot free) RNA secondary structures in a single RNA molecule. Over the years, it has been extended to cover pseudoknots (of possibly higher orders) using matched pairs of [], {}, and <> etc.

To derive dbn from three-dimensional atomic coordinates with DSSR, I was faced with an issue on how to represent multiple RNA chains (molecules). A closely related yet practical problem is chain breaks, as in x-ray crystal structures where disordered regions may not have fitted coordinates. I searched but failed to find any ‘standard’ way to account for chain breaks or multiple molecules in dbn. The commonly used programs for visualizing RNA secondary structure diagrams that I tested at that time did not take such cases into consideration — they simply showed all bases as if they were from a single continous RNA chain.

I discussed the issue with Dr. Yann Ponty, the maintainer of the popular VARNA program. After a few around of email exchanges, we introduced an extra symbol (&) in both sequence and dbn to designate multiple chains or breaks within a chain to communicate between DSSR and VARNA.

As an example, the DSSR-derived dbn for the double-stranded DNA structure 355d (the famous Dickerson dodecamer) is as below:

Secondary structures in dot-bracket notation (dbn) as a whole and per chain

>355d nts=24 [whole]

CGCGAATTCGCG&CGCGAATTCGCG

((((((((((((&))))))))))))

>355d-A #1 nts=12 [chain] DNA

CGCGAATTCGCG

((((((((((((

>355d-B #2 nts=12 [chain] DNA

CGCGAATTCGCG

))))))))))))

As another example, the PDB entry 2fk6 contains a tRNA with chain breaks — nucleotides 26 to 45 are missing from the structure (see figure below). The DSSR-derived dbn is as follows — note the * at the end of the header line.

>2fk6-R #1 nts=53 [chain] RNA*

GCUUCCAUAGCUCAGCAGGUAGAGC&GUCAGCGGUUCGAGCCCGCUUGGAAGCU

(((((((..((((.....[..))))&...(((((..]....)))))))))))).

It is worth mentioning a subtle point in DSSR-derived dbn with multiple chains, i.e., the order of the chains may make a difference! The point is best illustrated with a concrete example — here, 4un3, the crystal structure of Cas9 bound to PAM-containing DNA target. Based on the data file downloaded directly from the PDB (4un3.pdb), the relevant portions of DSSR output are:

****************************************************************************

Special notes:

o Cross-paired segments in separate chains, be *careful* with .dbn

****************************************************************************

This structure contains *1-order pseudoknot

o You may want to run DSSR again with the '--nested' option which removes

pseudoknots to get a fully nested secondary structure representation.

o The DSSR-derived dbn may be problematic (see notes above).

****************************************************************************

Secondary structures in dot-bracket notation (dbn) as a whole and per chain

>4un3 nts=120 [whole]

AUAACUCAAUUUGUAAAAAAGUUUUAGAGCUAGAAAUAGCAAGUUAAAAUAAGGCUAGUCCGUUAUCAACUUGAAAAAGUG&CAATACCATTTTTTACAAATTGAGTTAT&AAATGGTATTG

((((((((((((((((((((((((((..((((....))))....))))))..(((..).)).......((((....)))).&[[[[[[[[))))))))))))))))))))&...]]]]]]]]

>4un3-A #1 nts=81 [chain] RNA

AUAACUCAAUUUGUAAAAAAGUUUUAGAGCUAGAAAUAGCAAGUUAAAAUAAGGCUAGUCCGUUAUCAACUUGAAAAAGUG

((((((((((((((((((((((((((..((((....))))....))))))..(((..).)).......((((....)))).

>4un3-C #2 nts=28 [chain] DNA

CAATACCATTTTTTACAAATTGAGTTAT

[[[[[[[[))))))))))))))))))))

>4un3-D #3 nts=11 [chain] DNA

AAATGGTATTG

...]]]]]]]]

The notes in the DSSR output is worth paying attention to. Specifically, it reports a “*1-order pseudoknot” — note also the *! Here the target DNA chain C comes before DNA chain D in the PDB file. The 5′-end bases in chain C pair with bases in D, and the 3′-end bases in C pair with RNA bases in chain A. There exist pairs crossing along the ‘linear’ sequence position-wise, hence the reported “pseudoknot”. However, simply reverse DNA chains C and D, i.e., moving chain D before C (in file 4un3-ADC.pdb), the “pseudoknot” will be gone, as shown below:

****************************************************************************

Secondary structures in dot-bracket notation (dbn) as a whole and per chain

>4un3-ADC nts=120 [whole]

AUAACUCAAUUUGUAAAAAAGUUUUAGAGCUAGAAAUAGCAAGUUAAAAUAAGGCUAGUCCGUUAUCAACUUGAAAAAGUG&AAATGGTATTG&CAATACCATTTTTTACAAATTGAGTTAT

((((((((((((((((((((((((((..((((....))))....))))))..(((..).)).......((((....)))).&...((((((((&))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

>4un3-ADC-A #1 nts=81 [chain] RNA

AUAACUCAAUUUGUAAAAAAGUUUUAGAGCUAGAAAUAGCAAGUUAAAAUAAGGCUAGUCCGUUAUCAACUUGAAAAAGUG

((((((((((((((((((((((((((..((((....))))....))))))..(((..).)).......((((....)))).

>4un3-ADC-D #2 nts=11 [chain] DNA

AAATGGTATTG

...((((((((

>4un3-ADC-C #3 nts=28 [chain] DNA

CAATACCATTTTTTACAAATTGAGTTAT

))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

Notes added on March 19, 2015

- It has drawn to my attention that the NUPACK uses ‘+’ instead of ‘&’ as the symbol to separate multiple chains (or chain breaks). In fact, DSSR has an undocumented option

--dbn_break which can be set to any of the character in the string &.:,|+. The ‘&’ symbol was chosen for communication with VARNA which requires ‘&’, at least up to now. This is an excellent example showing the efforts that I have put into the little details while developing DSSR.

- The issue on proper ordering of multiple chains to avoid crossing lines (false pseudoknots) has been formally addressed by Dirks et al. in their 2007 article titled Thermodynamic analysis of interacting nucleic acid strands (SIAM Rev, 49, 65-88), specifically in Section 2.1 (Fig. 2.1). Applying that algorithm to nucleic acid structures, however, is beyond the scope of DSSR. The program strictly respects the ordering of chains and nucleotides within a given PDB or PDBx/mmCIF file, but outputs warning messages where necessary to draw users’ attention. As another example, I’ve recently noticed that DNA duplexes produced by Maestro (a product of Schrödinger) list nucleotides of the complementary strand in 3′ to 5′ order to match the 5′ to 3′ directionality of the leading strand for each Watson-Crick pair (See below).

****************************************************************************

Special notes:

o nucleotides out of order

****************************************************************************

Secondary structures in dot-bracket notation (dbn) as a whole and per chain

>ga62_ca62_1m_in nts=24 [whole]

GGCGAATTCCGG&C&C&G&C&T&T&A&A&G&G&C&C

((((((((((((&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)

>ga62_ca62_1m_in-1-A #1 nts=12 [chain] DNA

GGCGAATTCCGG

((((((((((((

>ga62_ca62_1m_in-1-B #2 nts=12 [chain] DNA

C&C&G&C&T&T&A&A&G&G&C&C

)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)&)

I’m going to attend the Biophysical Society (BPS) 59th Annual Meeting to be held during February 7-11 at Baltimore, Maryland. In last year’s BPS annual meeting (San Francisco, California), I was delighted to come across a few 3DNA users at poster sessions. I thought this post may help to connect me with some DSSR/3DNA users in the coming meeting.

Want to have a meetup at Baltimore? Please drop me a message!

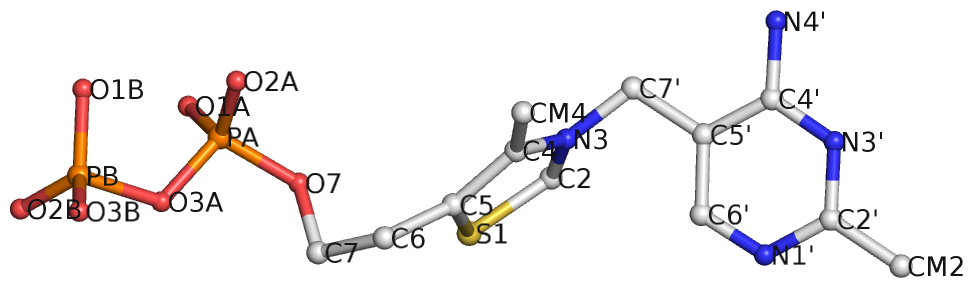

Recently I came across the ligand thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) in some RNA riboswitch structures. I was a bit surprised by the atom names adopted for the ligand by the PDB. See figures below for the chemical structure of TPP from the RCSB PDB website (first), and the three-dimensional structure of the ligand from the riboswitch 2gdi (second).

Specifically, the planar base-like moiety at the right has atom names ending with prime. To my knowledge, only sugar atom names of DNA and RNA nucleotides have the prime suffix, such as the 2′-hydroxyl group in RNA.

The RCSB webpage for TPP shows that currently there are 107 entries in the PDB, among which 100 are from proteins, 6 from RNA, and one in a RNA-protein complex. It is not clear to me whether the prime-bearing names in TPP are following any documented ‘standard’ or convention. DSSR is nevertheless taking a note of such ‘weird’ cases.